SEATTLE (AP) — Doctors who specialize in female pelvic medicine say lawsuits by four states, including Washington and California, over products used to treat pelvic floor disorders and incontinence might scare patients away from the best treatment options — or maybe even push the products off the market.

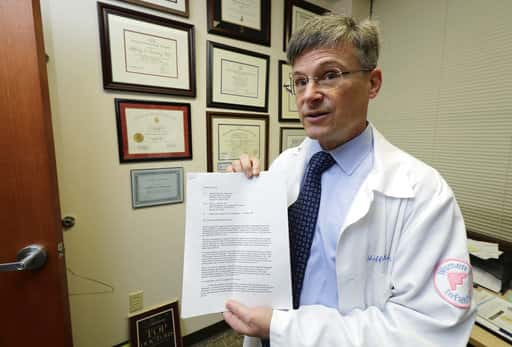

Sixty-three Washington surgeons signed a letter to state Attorney General Bob Ferguson , arguing his consumer-protection lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson and its Ethicon Inc. subsidiary is off-base. The lawsuit says the companies failed to disclose risks associated with the products, but in their letter the doctors said they were never deceived and that the case is based on a misconception about how they assess dangers posed by medical procedures.

“We have served on national and regional medical societies in women’s health,” wrote Dr. Jeffrey Clemons, a pelvic reconstructive surgeon in Tacoma. “It is astonishing to us that the AG is proceeding with this lawsuit without first availing themselves of the significant experience and expertise of this group.”

Doctors in California are drafting a similar letter to Attorney General Xavier Becerra, and the president of the American Urogynecologic Society, which represents 1,900 medical professionals, has issued a statement expressing some of the same concerns.

Clemons and two other doctors who signed the Washington letter have been retained by defense counsel as consultants in the case, but Clemons said he wrote it without payment or assistance from Johnson & Johnson.

At issue is “transvaginal mesh” — plastic mesh products that are implanted to correct a variety of pelvic floor disorders.

They came on the U.S. market in the late 1990s to treat stress urinary incontinence — a condition triggered by physical activity like coughing, sneezing or running that is common and sometimes debilitating in women after childbirth. The treatment involves using a thin mesh strip, called a “mid-urethral sling,” to support the urethra, the tube that carries urine away from the bladder.

The products were so successful — one of the most significant advances in women’s health in recent decades, the physicians said — that companies began developing similar mesh products to treat another condition, called pelvic organ prolapse.

In such cases, pelvic organs such as the uterus and bladder drop from their normal position due to muscle weakening. A sheet of mesh can be used to support the pelvic floor.

However, treating pelvic organ prolapse with mesh proved problematic after those products were introduced in 2004. They were more likely to bring serious complications, including permanent incontinence, severe discomfort and an inability to have sex.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued warnings in 2008 and 2011, and companies pulled most of the transvaginal mesh products for organ prolapse from the market.

Tens of thousands of women have filed liability claims against Johnson & Johnson and other companies, with some saying they knew nothing about the potential complications.

The doctors say Washington’s lawsuit conflates the acceptable risks of using pelvic mesh to treat incontinence with the less tolerable risks of using it for pelvic organ prolapse. They’re worried it could force mid-urethral slings off the market, though the attorney general’s office says that’s not the goal.

Washington, California, Kentucky and Mississippi are pursuing lawsuits that claim Johnson & Johnson deceived doctors and patients, and that the surgeries ruined some women’s quality of life. They say product marketing brochures and instruction pamphlets should have contained much more detail about the risks.

The company updated its instruction pamphlets in 2015 — effectively admitting the earlier versions were inadequate, Washington state says.

“The purpose of our lawsuit is to require Johnson & Johnson to disclose to doctors and patients the serious risks associated with surgical mesh,” Ferguson said in an emailed statement. “Johnson & Johnson knew about these risks for years and misrepresented them for more than a decade, even as it sold thousands of these devices in Washington.”

Washington’s lawsuit seeks fines for each alleged violation of the state’s Consumer Protection Act, an amount that could easily run into the millions. The attorney general’s office also wants to bar Ethicon from representing that its surgical mesh is superior to traditional treatments, such as repair using the patient’s tissue, and it says a key question is whether the pamphlets could have deceived the least sophisticated surgeons, not the most sophisticated.

In their letter last month, the surgeons insist they were never misled — nor could they have been, because they don’t rely on a company’s marketing materials or instruction pamphlets to divine the risks of medical devices.

Instead, the letter said, they rely on their education, journals, conferences, textbooks and other unbiased sources, and they counsel their patients accordingly.

In declarations filed in King County Superior Court, some said Ethicon paid for them to undergo training that fully explored the devices’ risks, and others said they learned about the uses and risks from those specially trained doctors.

Clemons and the other surgeons do not dispute that some women have suffered complications from the use of mesh to treat incontinence, but they say any surgery has risks, and the risks of that procedure are well within accepted norms. Millions of women worldwide have been treated with mid-urethral slings.

The letter cited a recent large study of the English National Health Service database that found complications prompted the removal of mesh slings in just 1.4 percent of patients within the first year after surgery, 2.7 percent within five years and 3.3 percent within nine years.

In fact, Clemons said, the mid-urethral sling has become the “gold standard” among surgical options for stress urinary incontinence because it offers better outcomes than other types of surgery, can be performed on heavier patients who otherwise would be ineligible for surgery, and requires less cutting and recovery time.

The Washington Attorney General’s Office said in a court filing the fact that doctors obtain also risk information elsewhere does not excuse the companies from ensuring their instructional pamphlets are “truthful and complete.”

The office agreed that many women have had positive outcomes with the devices and said it does not seek to restrict access to them.

Nevertheless, the state is relying on an expert witness, Dr. Bruce A. Rosenzweig, a gynecologist at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, who insisted in a deposition that polypropylene mesh is an “unsafe material to be placed permanently in the female pelvis.” That position is contrary to the scientific literature, according to the surgeons’ letter.

Clemons is a retired Army colonel who spent a decade as the chief of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Madigan Army Medical Center. He serves on the board of the American Urogynecologic Society and has performed about 1,250 mid-urethral sling surgeries; he used to cut his own mesh slings before Ethicon’s came on the market.

After filing the lawsuit, the Washington Attorney General’s Office tried to recruit him as an expert witness, he said. Although he is a fan of Ferguson’s Democratic politics — Clemons donated $550 to his re-election campaign last month — he declined.

“I’m not anti-Bob Ferguson at all,” Clemons said. “I just disagree with him on this.”

___

Follow Gene Johnson at https://twitter.com/GeneAPseattle